Image source: click here

Papua New Guinea is a nation known for its abundance of tropical forests and biodiversity. New Guinea itself is home to the third largest rainforest in the world, shared by Papua New Guinea and the Indonesian provinces. This rainforest is also home to extremely unique wildlife. For example, tree kangaroo species are only found in the forests of Papua New Guinea, West Papua and Australia. Several Indigenous tribes also call Papua New Guinea’s forests home, as they have for generations. The inhabitants of Papua New Guinea’s forests are being threatened by extensive deforestation and forest degradation. This is in large part due to increases in logging, mining activities and urban development. Therefore, it is becoming increasingly important to address and assess environmental threats and destruction to Papua New Guinea’s forests and the biodiversity it houses.

Papua New Guinea Forest Protection, Conservation and UN REDD+

The United Nation’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (UN REDD+) strategy was first discussed in 2005 at the request of Costa Rica and Papua New Guinea. The funding of the strategy in large part comes from industrialized nations such as Denmark, Switzerland, Norway, Japan, Luxembourg and Spain. In 2008, the strategy was officially launched to assist developing nations such as Papua New Guinea in reaching the goals of REDD+. The four elements of Papua New Guinea’s national framework include incorporating the viewpoints of national stakeholders, a national monitoring system, a forest reference level and a safeguard information system. This is all in an effort to achieve sustainable development, environment and address climate change. This program has made significant efforts to strengthen Papua New Guinea’s institutional capacity to monitor and mitigate the loss of their forests. However, the UN REDD+ program has been critiqued. The funding is provided from a limited number of industrialized nations and the compilation of roughly 350 UN REDD+ programs and projects has had mixed results and impact (Mongabay 2020). In October, 2019 a lack of funding to UN REDD+ programs in Papua New Guinea was noted by Dr. Ruth Turia, the director of Papua New Guinea’s forest authority. According to Dr. Turia there have been challenges implementing REDD+ activities, as their monetary value often cannot be compared to activities threatening forest existence such as logging. There have also been issues with institutional arrangement of REDD+ programs and land tenure in order to carry out the strategy’s activities in Papua New Guinea. Dr. Turia has recommended to evaluate experiences, training and technologies that have been used in different areas in order to improve regional cooperation in UN REDD+ activities, along with allocating technical and financial support based on regional needs in forest protection. Though the UN REDD+ strategy’s top down financial support and programing does have positive impacts, its struggles also indicate a need to engage and receive support from local people, local governments and organizations.

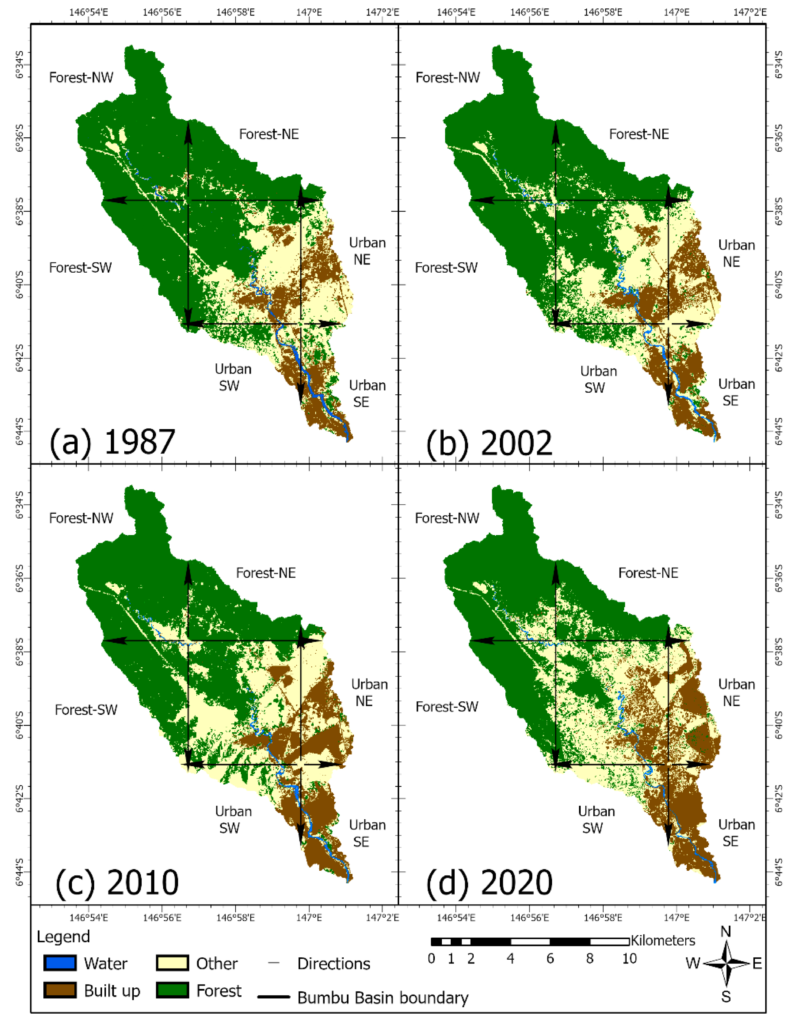

An article published on August 20th, 2020 in the MDPI Journal’s Land 2020 Volume has been written in collaboration with the Morobe Development Foundation and it’s volunteers. Herein, the authors (Willie Doaemo, Midhun Mohan, Esmaeel Adrah, Shruthi Srinivasan, and Ana Paula Dalla Corte) assessed changes in forest coverage in the Bumbu River Basin area over a 33 year period from 1987 to 2020 using satellite imagery and Geographic Information System tools; Google Earth images were utilized to verify the accuracy of classification results. The study specifically assessed images of four areas in the Bumbu River Basin (located in the vicinity of Lae city – the second largest city in Papua New Guinea) during the years 1987, 2002, 2010 and 2020 and the findings provide insight into the area’s increasing land use land cover (LULC) change patterns leading to deforestation and forest degradation. The results indicate a steady decrease in forest area in the Bumbu River basin over the period studied. Forest area has dropped from 62.33% in 1987 to 57.26% in 2010 and now 48.55% in 2020.

Image source: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/9/9/282

Built up areas and agricultural expansion were expected to be partial causes of this decrease. In addition, urbanization was reported to be rapidly increasing during the 2010-2020 period causing a loss in forest area. What makes this study by Doaemo et al., 2020 unique is that it underscores the potential influence of urbanization and agricultural land expansion in forest loss at Bumbu watershed area whereas previous studies focused primarily on the impact of subsistence agriculture while dealing with deforestation studies in Papua New Guinea. This study also highlights a need to repeat their research to evaluate if a similar trend exists at the national level. In tandem, the proceedings of the aforementioned endeavor add to the literature which demonstrates how remote sensing technologies such as satellite imagery can be used to evaluate and assess forest coverage and greenhouse gas emissions, which further contributes to the success or progress of climate change mitigations programs such as the UN REDD+.

As noted in the discussion section of this article, more attention and resources need to be directed towards forest monitoring and involvement of the public, local level, government and NGOs is crucial for enhancing forest conservation initiatives aimed at protecting and preserving Papua New Guinea’s priceless flora and fauna.

Sources:

Doaemo, Willie, Midhun Mohan, Esmaeel Adrah, Shruthi Srinivasan, and Ana Paula Dalla Corte. “Exploring Forest Change Spatial Patterns in Papua New Guinea: A Pilot Study in the Bumbu River Basin.” Land 9, no. 9 (September 2020): 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9090282.

UN News. “FROM THE FIELD: Saving the Tree Kangaroos of Papua New Guinea,” May 20, 2019. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/05/1038811.

REDD+. “Home Page.” Accessed September 13, 2020. http://pngreddplus.org.pg/.

Patjole, Cedric. “Lack of Funding for REDD+ Activities.” Loop PNG, October 4, 2019. https:/node/87360.

“Local Action to Protect Biodiversity: The Tree Kangaroo in Papua New Guinea | Global Environment Facility.” Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.thegef.org/news/local-action-protect-biodiversity-tree-kangaroo-papua-new-guinea.

“New Guinea | WWF.” Accessed September 13, 2020. https://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/where_we_work/new_guinea_forests/.

ABE, Hitofumi. “Papua New Guinea’s REDD+ Journey.” un-redd-website, September 3, 2018. https://www.un-redd.org/post/2018/09/03/papua-new-guinea-s-redd-journey.

“Papua New Guinea’s REDD+ Journey | REDD+ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.” Accessed September 13, 2020. http://www.fao.org/redd/news/detail/en/c/1156446/.

UNDP in Papua New Guinea. “PNG Forests Key to Fighting Climate Change and Advancing Development.” Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.pg.undp.org/content/papua_new_guinea/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2015/03/20/png-forests-key-to-fighting-climate-change-and-advancing-development.html.

Mongabay Environmental News. “The U.N.’s Grand Plan to Save Forests Hasn’t Worked, but Some Still Believe It Can,” July 14, 2020. https://news.mongabay.com/2020/07/u-n-s-grand-plan-to-save-forests-hasnt-worked-but-some-still-believe-it-can/.

un-redd-website. “UN-REDD Programme | Donors.” Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.un-redd.org/donors.

0 Comments