Image source: click here

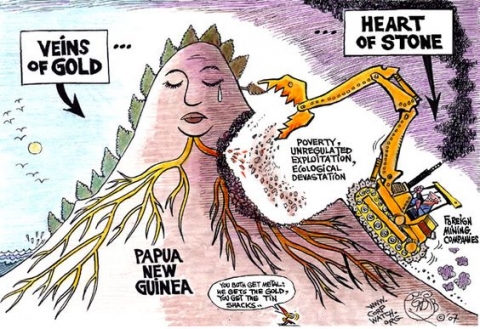

The Mining Situation in Papua New Guinea

- The highlands of Papua New Guinea have been open to mining activities since the 1980s.

- The industry has significantly contributed to the growth of Papua New Guinea’s economy, as according to World Wildlife Fund it is the second largest employer of citizens in the nation (2020).

- The Papua New Guinea Government has recently refused to extend the Canadian mining company Barrick Gold Corporation’s lease due to social and environmental concerns.

- Non profit organizations have also pushed for an international moratorium against deep sea mining as it will have detrimental and irreversible damage to Pacific island nations such as Papua New Guinea.

Papua New Guinea Mining Stakeholders – An Analysis

The growth of Papua New Guinea’s mining industry has significantly affected the lives and livelihoods of their Indigenous peoples and the environment. There are different theorizations and meanings of land held by Indigenous peoples, the government and the mining companies related to “agency as power” and “culturally defined projects”. I argue that Indigenous people, the government and mining companies do have different meanings associated with land, and western parties do demonstrate agency as power over Indigenous groups regarding legal definitions of landownership and environmental destruction. However, Indigenous peoples are not helpless or hopeless in the context of mining activities, indicating parties involved in mining activities may also pursue the same “culturally defined project”.

Below are some definitions of terms/ concepts which are useful when analyzing power dynamics and intentions of stakeholders and actors in Papua New Guinea’s mining industry:

- Place may be understood according to an article by McIlwraith and Cormier (2016) – which refers to the centre of intention, action and individual experience at a particular location.

- Place is also a reality to be clarified and understood from the perspectives of the people who have given it meaning according to Tuan (1979).

- Space is more abstract, quantifiable and locational.

- Land may be understood according to the definition given by Jennette Armstrong (2009) which states aboriginal land “encompasses culture, relationships, ecosystems, social systems, spirituality and law”.

- Agency refers to the individual acting within their cultural structures (Ortner 2006).

- Agency as power, refers to the ability to act within social inequality, asymmetry and force.

- Culturally defined projects refers to culturally formed and structured goals, desires and intentionality according to Sherry Ortner (2016).

Based on my analysis of ethnographic studies and articles about Indigenous peoples and their land located in the vicinity of mines in Papua New Guinea, I argue that the Indigenous groups in my ethnographic examples understand their land and territory more in terms of “place”. This is due to their oral histories, kinship relations associated with landownership and sacredness of the land as expressed in mythologies. For example, each Ipili indigenous kin group has sacred sites on their land where ancestral spirits reside, and where sacrifices in honour of those spirits are made (Golub 2014). Furthermore, Telefolmin Indigenous people trace their descent in the area from their ancestress known as Afek, and because the Telefolmin looked after Afek’s spiritual house they were given ritual superiority over the region (Jorgensen 1997). This mythological, ancestral and ritual connection to the region was honoured by the Australian administration’s settlement in Nenataman after the Second World War, as the centre location of the colonial authority reaffirmed the Telefolmin myth’s positioning of relations (Jorgensen 1997).

Also, the Telefolmin and Wopkaimin people believe the mineral deposits found on the mountain in their region were once the site of Afek’s established “Land of the Dead” (Jorgensen 1997: 603; Hyndman 1994). These examples illustrate how Indigenous perceptions of land are grounded in social relations, perceived as a sacred gift (Jacka 2001).

I also found the Papua New Guinea government and mining companies viewed the Indigenous land in terms of “space”. The territory is quantifiable as its resources may be worth a specific amount of money. It is also locational as mineral resources have only been found in that particular area. It is also important to consider how the mining prospectors view this “space” in terms of utility and extraction. The establishment of mining operations at Porgera valley has made the region identifiable with technologically advanced mining operations and as having the third most productive gold mine in the world – rather than the valley being associated with Indigenous understandings of place, land and culture (Banks 1997 as cited in Golub 2014). Also, as Indigenous hunting, gardening and cultivation practices do not disturb the landscape, it gives the government and companies the impression the land is actually not being used- just simply empty space. Government and mining companies’ perceptions of productive use of “space” are important to consider along with their business and capitalist interests.

I found “agency as power” was evident in ethnographic accounts and descriptions of interactions between governments, mining companies and Indigenous groups. The Ipili indigenous people view the mining companies and westerners as part of their designated cultural category of the “whiteman” which has connotations of power, domination and greed (Jacka 2007: 445). The Ipili have given up their land, the right to mine this resource themselves and have received little in return (Jacka 2007). This has prompted a significant amount of the population to refer to the “whitemen” and mining companies as greedy “pigs” who consume all the gold (Jacka 2007: 448).

The mining activities have destroyed their environment and livelihoods. The government also demonstrates “agency as power” as they have the legal power to lease indigenous land for mining projects whether the people consent to it or not. They also define who owns the land and receives benefits from being displaced based on the notion of clan which does not adequately encompass the ambiguous social relations of many groups, such as the Ipili Indigenous people.

Image source: click here

Indigenous territories with sacred and meaningful legacies are subjected to the destructive nature of mining activities. Porgera mountain is an open cut mine with huge excavations digging away at the mountain side (Golub 2014). In the year 2000, Ipili landowners only had to walk a short distance from the ridge of their property before falling into the open mining pit (Golub 2014). Furthermore, the land shortage caused by mining activities has negatively impacted the subsistence agricultural output and has made many inhabitants in the Porgeran region dependent on distributed mine benefits to purchase food (Golub 2014). Also, more than 95% of the contents extracted become tailing residue containing harmful substances such as lead, mercury and arsenic which are released into the Porgera River, contributing to its reddish tinge (Golub 2014). This has contributed to degradation and contamination of fish and livestock populations (Earthworks 2012).

Image of mining pollution in Pongema River – source: click here

Despite these instances of hardship and domination, the Ipili and other Indigenous groups for example in some cases do not feel dominated. They have politically advocated for their compensation and rights in the process. In fact, they enjoy the modern houses they are relocated to as a result of their land being mined, the material wealth and mining occupations they may have (Golub 2014). The Ipili legally defined as landowners that do receive compensation have also formed their own unique “elite” class (Golub 2014). Therefore, the pursuit of mining activities, wealth and economic growth – a dominant “culturally defined project” are not only for the government and mining companies but also for some Indigenous groups as I have mentioned. This could also indicate cultural change in culturally defined project pursued by Papua New Guinea’s Indigenous groups as a result of capitalist expansionism.

How can NGOs help?

After this research and analysis, I was left with the impression NGOs could definitely work towards assisting local and Indigenous populations manage changes and threats to their income, land and food security as a result of mining activities. The environmental impact of mining is also staggering and detrimental, therefore methods to achieve ecological restoration through sustainable agricultural practices, replanting, and the rethinking and redesigning of mining activities could be goals of NGOs wanting to address this issue. The Morobe Development Foundation is committed to addressing issues in PNG regarding food security and climate change, as evident in previous projects. Addressing mining related community impacts could be the focus of future projects at MDF.

References

Armstrong, J. 2009 ‘Land & Rights’. indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca, https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/land__rights/.

C, Jamasmie. Fresh study calls for moratorium on deep-sea mining. Mining [dot] com. May 20 2020. https://www.mining.com/fresh-study-calls-for-moratorium-on-deep-sea-mining/

Barrick Gold sends dispute notice to Papua New Guinea over Porgera mine / Reuters / July 10 2020 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-barrick-gold-png/barrick-gold-sends-dispute- notice-to-papua-new-guinea-over-porgera-mine-idUSKBN24B188

Earthworks and MiningWatch Canada. 2012 “Troubled Waters: How Mine Waste Dumping Is Poisoning Our Oceans, Rivers and Lakes,”

Golub, A. 2014 Leviathans at the gold mine: Creating indigenous and corporate actors in Papua New Guinea. Duke University Press.

Hyndman, David. 1994. ‘A Sacred Mountain of Gold: The Creation of a Mining Resource Frontier in Papua New Guinea ∗’. The Journal of Pacific History 29(2): 203–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223349408572772.

Jacka, J. K. 2007.“Whitemen, the Ipili, and the City of Gold: A History of the Politics of Race and Development in Highlands New Guinea.” Ethnohistory 54, no. 3: 445–72. https://doi.org/10.1215/00141801-2007-003.

Jorgensen, Dan. 1997 ‘Who and What Is a Landowner? Mythology and Marking the Ground in a Papua New Guinea Mining Project’. Anthropological Forum 7(4): 599–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.1997.9967476

McIlwraith, Thomas, and Raymond Cormier. 2015/2016 Making Place for Space: Land Use and Occupancy Studies, Counter- Mapping, and the Supreme Court of Canada’s Tsilhqot’in Decision. BC Studies. No 188:35-53.

Ortner, Sherry B. 2006 Power and Projects: Reflections on Agency (Chapter 6), Anthropology and Social Theory: Culture, Power, and the Acting Subject. Durham: Duke University Press. P. 129- 153.

Tuan, Yi-Fu.1979. “Space and place: humanistic perspective.” In Philosophy in geography, pp. 387- 427. Springer, Dordrecht.

World Wildlife Fund. 2020. Mining in New Guinea. https://wwf.panda.org/knowledge_hub/where_we_work/new_guinea_forests/problems_forests_new_guinea/mining_new_guinea/, accessed March 28, 2020

0 Comments